Japanese Asset Bubble: Lessons from the Economic Asset Bubble of Japan, The Heisei Boom. What parallels exist between the Japanese asset bubble and our current financial environment?

It is hard to believe that we have learned so little from previous asset bubbles. Many of our policymakers have turned a blind eye to the Great Depression, euphorically thinking that somehow all variables of risk had been eliminated from the system. It would be one thing to acknowledge our current predicament and at least try something different from the past to combat the current financial demons we are facing. Instead, we are using policy moves from the past that had little impact in resolving financial problems.

This is primarily occurring with massive focus on lending institutions and banks. The Federal Reserve with the leadership of Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke have focused tremendous energy on this sector while ignoring virtually all historical examples where this failed. Primarily, with the asset bubble of Japan that occurred from 1987 to 1990 and created nearly two lost decades of economic productivity. In today’s article we are going to exam a research paper published by the Bank for International Settlements that was presented in October of 2003 at the International Monetary Fund.

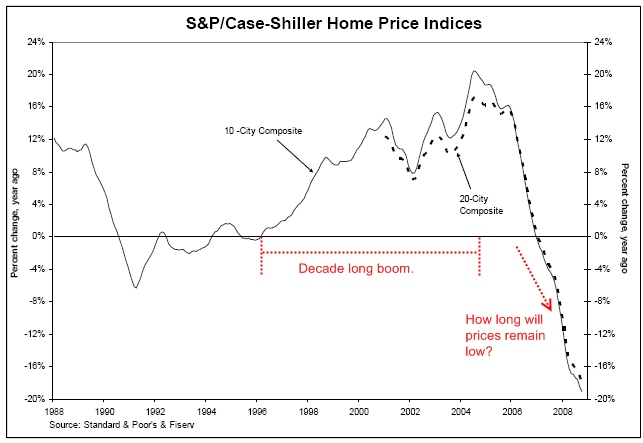

It is important to first look at what stage we are in regarding our current asset bubble:

For over a decade not only did asset prices increase, they went into an unsupportable range. The challenge now and the question most have on their mind is at what level will prices reach a supportable bottom? After all, year over declines for the Case-Shiller Index didn’t start until 2007. If we look at the Japanese asset bubble, prices went down for well over a decade. Are we ready as a nation to see stagnant real estate prices until 2019? It sure makes my prediction of a bottom in California of 2011 seem optimistic.

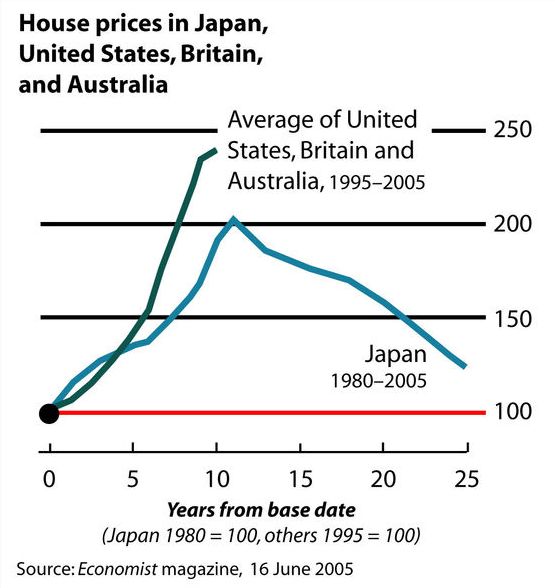

Let us first take a look at this current real estate bubble versus that of Japan:

*Source:Â Economist

This current real estate bubble is already larger in scope than that of Japan. I’ve seen a few people argue more narrowly that Tokyo prices went much higher than anything we have seen here in the United States:

*Source:Â Debt Deflation

That is true. Yet if we look at individual markets like that of Los Angeles for the Case-Shiller Index we get an index number of 273 at the peak. Keep in mind the Case-Shiller Index for L.A. looks at Los Angeles and Orange County. If we would segment niche markets here, we will find areas that saw an index above 300, that is certain. Yet looking at the first Economist chart, we realize that nationwide we have a much bigger bubble here. If that is the case, why should we expect a short recovery?

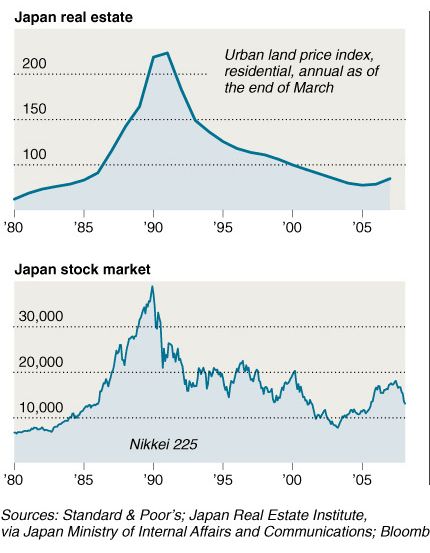

Given that we are now in a zero interest rate policy universe, Japan is looking more and more like an apt comparison. We have a country that had both a stock market and real estate bubble both bursting at the same time. We had financial deregulation, low interest rates, and a tremendous amount of euphoria fueling an epic real estate bubble. Sounds familiar? Well what about billions of capital injections into banks causing zombie institutions dragging growth down for almost 2 decades?

Let us examine crucial parts of the paper:

“What should be noted regarding Japan’s experience is that the enthusiasm of market participants, together with the inconsistent projection of fundamentals, contributed to a large degree to maintaining temporarily high asset prices at that time. Such enthusiasm is often called euphoria, excessively optimistic but unfounded expectations for the long-term economic performance, lasting for several years before dissipating.”

“It was thus excessive optimism rather than consistent projection of fundamentals that mainly supported temporarily high asset prices.”

So on this point, we are similar. That is, market fundamentals had nothing to do with price rises and the justification given for the boom was usually excessive optimism transmitted by “real estate never goes down” or some other form of delusional thinking. This kind of thinking on a very short-term basis rarely is a threat to the economy as a whole but letting this kind of thinking continue for a decade is extremely problematic.

“First, at the time of the Iwato boom, when Japan’s economy entered the so-called “high economic growth period”, asset prices increased rapidly, reflecting an improvement in fundamentals due to technological innovations. The real economic growth rate exceeded 10% per annum, driven mainly by investment demand due to technological innovations that replaced the post World War II reconstruction demand. On the price front, consumer prices rose while wholesale prices remained generally stable, thus leading to the so-called “productivity difference inflation”.

“Kakuei Tanaka, who became Prime Minister in 1972, effected extremely aggressive public investment based on his belief (remodelling the Japanese archipelago) that it was necessary to resolve overpopulation and depopulation problems by constructing a nationwide shinkansen railway network, which led to an overheated economy.”

Interestingly enough, we also get an idea that two booms can happen relatively quickly. The Iwato boom occurred first later paving the way for the Heisei boom or the boom that occurred from 1987 to 1990. The language from the Iwato boom is very much similar to our technology driven boom of the 1990s where much of the euphoria was driven by new technological innovations. What this tells us is psychologically, Japan and the U.S. had similarities viewing these booms and also that consumer behavior is largely universal in many respects. One fueled by technological prowess and the other based on excessive optimism.

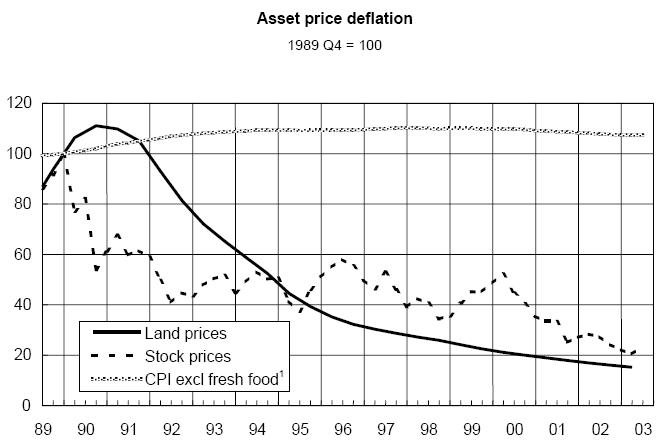

“Third, in the Heisei boom, asset prices increased dramatically under long-lasting economic growth and stable inflation. Okina et al (2001) define the “bubble period” as the period from 1987 to 1990, from the viewpoint of the coexistence of three factors indicative of a bubble economy, that is, a marked increase in asset prices, an expansion in monetary aggregates and credit, and an overheating economy. The phenomena particular to this period were stable CPI inflation in parallel with the expansion of asset prices and a long adjustment period after the peaking of asset prices.”

“The decline in asset prices was initially regarded as the bursting of the asset price bubble, and an amplifying factor of the business cycle. Although the importance of cyclical aspects cannot be denied, further declines in asset prices after the mid-1990s seem to reflect the downward shift in the trend growth rate beyond the boom-bust cycle of the asset price bubble.”

This boom and bust is clearly depicted by the bursting of the Nikkei and Japanese land prices:

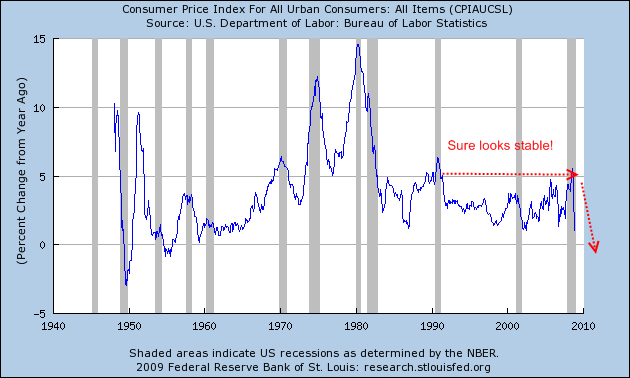

Here we have another similarity. That of “stable” inflation paving the way for a continuation of relaxed monetary policy. As I have highlighted before the CPI is a sham and does very little reflecting the actual reality during the boom. Also, unemployment is poorly reflected. Why is that? Unemployment numbers leave a large section of our employment base out, those not looking for work and those underemployed. The CPI uses the OER measure or owner’s equivalent of rent to measure housing. This of course practically left out the entire real estate bubble from the CPI measures! So housing was understated from the CPI for nearly a decade and being a large portion of the CPI, it skewed the measure lower. Take a look at the CPI for this time period:

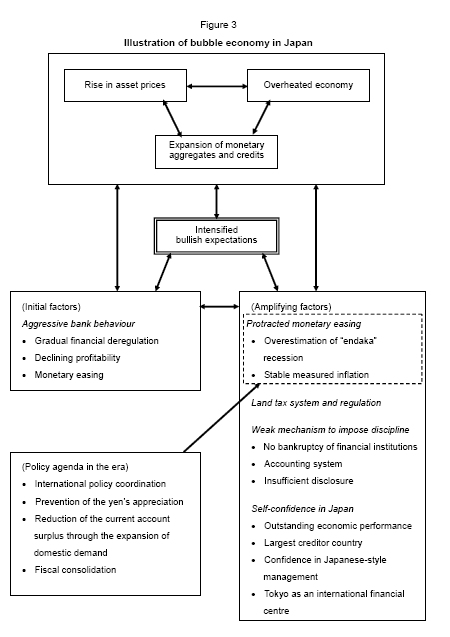

Well of course, inflation looks stable when you don’t accurately measure the true growth in asset prices. Just look at the Case-Shiller Index and you’ll realize there is a major disconnect. The government also for a long time was looking at the OFHEO housing numbers which of course, only looked at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac or other conforming government loans which entirely misses the boom with toxic pay option arms, subprime mortgages, and other interest only products. So what you are left with is poor measures of inflation and housing prices and government policy basing decisions on this terrible information. Yet the reasons given in the paper presented at the IMF for the Japanese asset bubble seem very familiar:

“The intensified bullish expectations were certainly grounded in several interconnected factors. The factors below are often pointed out as being behind the emergence and expansion of the bubble: • aggressive behaviour of financial institutions

• progress of financial deregulation

• inadequate risk management on the part of financial institutions

• introduction of the Capital Accord

• protracted monetary easing

• taxation and regulations biased towards accelerating the rise in land prices

• overconfidence and euphoria

• overconcentration of economic functions in Tokyo, and Tokyo becoming an international financial centre

Focusing on monetary factors, it is important to note the widespread market expectations that the then low interest rates would continue for an extended period, in spite of clear signs of economic expansion. The movement of implied forward rates from 1987 to 1989 (Figure 5) shows that the yield curve flattened while the official discount rate was maintained at a low level.”

Well look at that. Aggressive behavior of financial institutions. Check. Progress of financial deregulation. Check. Inadequate risk management. Check. Protracted monetary easing. Check. Overconfidence and euphoria. Big freaking check. That is why Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke easing monetary purse strings during the euphoria stage was insanely irresponsible. The signs were already there. Yet simply looking at inflation via the CPI or housing prices via the OFHEO numbers painted a largely phony picture that we now know is true. That is, housing prices were increasing while incomes were stagnant and shadow asset inflation was exploding. How did this happen? Of course through more and more toxic mortgage products being fueled by an easy credit environment, much of it hidden through the securitization of the credit markets. If you want to see how the system in Japan was setup, look at this chart:

One major difference is Japan is largely a creditor nation while we are the largest debtor nation. How this changes the equation is largely unseen yet. You would think, that eventually the U.S. dollar with the Fed and U.S. Treasury determined to sink the value of our currency, would eventually show up in the system as a weaker dollar unfortunately. Yet last year, one of the few bright spots was the U.S. dollar. Why? First, the entire world went into a period of financial deleveraging. Central banks around the world almost uniformly started dropping rates. So if we drop rates by .25 points and so does every other nation, we largely offset one another. That is one major reason why we saw little change. It is also the case that the U.S. still is a safe haven for global capital. How long this will remain is largely unknown.

Yet we do know that we have reached the bottom in terms of monetary easing, at least the old school way of doing it. We are largely in a zero interest rate world. That weapon is now empty. Other central banks (not Japan) have more wiggle room so it will be interesting to see what occurs when they cut rates while we remain sidelined largely because we cannot do much more in the monetary realm. Of course we are practically assured a large fiscal program next year so it is hard to see what will happen. If Japan is any example, not much:

“The first lesson is that risks of financial and macroeconomic instability build up during asset price booms and materialise as an aftermath of asset price declines and recessions. In the light of Japan’s experience, it seems to be a characteristic that the effects of a bubble are asymmetrically larger in the bursting period than in the expansion period.

A rise and fall in asset prices, which contain an element of a bubble, influence real economic activity mainly through two routes: (i) consumption through the wealth effect, and (ii) investment through a change in the external finance premium due to changes in collateral and net asset values. As long as asset prices are rising, they influence the economy in a favourable way and the adverse effects are not thoroughly recognised.

However, once the economy enters a downturn, the above favourable cycle reverses, thereby leading to a severe reaction. The harmful effects of a bubble will emerge, exerting stress on the real side of the economy and the financial system due to an unexpected correction of asset prices. If intensified bullish expectations which previously supported the bubble are left unchecked, the expansion and subsequent bursting of the bubble will become more intense, affecting the real economy directly or, by damaging the financial system, indirectly.”

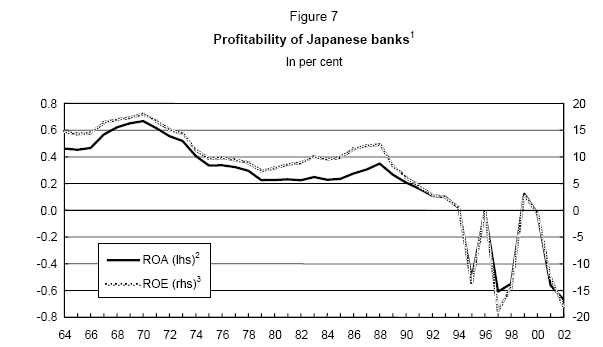

This is a key point. The bust of the bubble largely erased all gains during the boom and some. If we are to look at the growth over the past decade, we still have a long way to go even to reach a breakeven point. Yet the paper makes a fascinating observation that major asset bubbles causes more harm than good once we look at the net add/loss. We are already seeing consumption being hammered by the loss in wealth. And just like Japan, our financial system is largely damaged. Will we have a lost decade as well? How can that option not be on the table? We are injecting capital into largely unproductive banks who are now hoarding money to what end? To buy up other banks? To lend at low rates? Who will be their clientele? Borrowers with too much debt and stagnant wages? Profitability of banks will be sinking just like Japan:

“Looking at the land price problem from the viewpoint of the stability of the financial system, it was the risk brought about by the sharp rise in land prices and the concentration of credit in the real estate and related industries that were insufficiently perceived. During the bubble period, real estate was generally accepted as collateral. However, if the profitability of businesses financed by secured loans is closely related to collateral value, such loans become practically unsecured since profits and collateral value move in the same direction.”

Another important point. Much of the problems we are seeing are from banks and financial institutions having to realize the actual asset value of their portfolios. This is problematic when assets were largely brought onto the books in euphoric stages of the boom which now have to be realized at bust prices. Essentially this assures financial institutions are holding onto underwater loans.

“In a financial system, banks play a buffer role against short-term shocks by accumulating internal reserves when the economy is sound and absorbing losses stemming from firms’ poor business performance or bankruptcy during recession. Even though some risks cannot be diversified only at a particular point in time, such risks can nevertheless be diversified over time. In order to achieve a more efficient allocation of risks in the economy, it is deemed important to have not only markets for cross-sectional risk-sharing but also sufficiently accumulated reserves as a buffer for intertemporal risk-smoothing.

Such a risk-smoothing function of the banking sector, however, is difficult to maintain under financial liberalisation and more intense competition from financial markets. Intertemporal smoothing requires that investors accept lower returns than the market offers in some periods in order to obtain higher returns in others. Investors, however, would opt out of the banking system and invest in the financial markets, thereby deteriorating banks’ internal reserves. As a result, a risk-smoothing function is lost easily and suddenly once the economy encounters a shock that erodes banks’ net capital to the extent that it threatens their soundness.”

“The third lesson is that the effectiveness of the central bank’s monetary easing is substantially counteracted when the financial system carries problems stemming from the bursting of a bubble.”

This is a point where our financial institutions largely ignored risk. It is interesting that excess reserves for banks are only increasing because they are sucking up bailout money! That is, they are preparing for a problem that occurred a decade ago with money coming out today! That is much too late. That is why it is stunning we are going down the path of Japan. I’m not sure how we don’t face a lost decade (at least) since we are following the exact playbook. Injecting capital into banks. Large infrastructure projects. And what did it do for Japan? The Nikkei peaked on December 29, 1989 closing at 38,915.87. Currently the Nikkei is at 8,859, nearly 20 years later. That is a drop of 77 percent. Even with the Great Depression drop prices after 20 years were already approaching the peak set in 1929. 8,859 is a long way from 38,915 and I doubt in 5 years it will get even close to that. So what is worse here?

“First, an increase in non-performing loans erodes the net capital of financial institutions, resulting in a decline in risk-taking ability (credit crunch).”

“More precisely, during financial crises, financially stressed banks tend to have serious difficulties not only with lending, but also arbitraging and dealing. This hampers the transmission mechanism from the policy-targeted rate to longer-term rates, resulting in segmentation among various financial markets. Thus, it could be extremely important for a central bank to intervene in various financial markets to fix segmented markets, thereby restoring market liquidity and the proper transmission mechanism.”

Japan also had a credit crunch. So another check there. Yet the crunch occurs for legitimate reasons. There is a quick crash bringing together a bubble reality with that of actual reality. The only obvious outcome is a crunch. After all, the euphoria dies quickly and panic slowly starts to set in. That is what occurred in August of 2007. The same thing occurred in Japan. Once financial institutions realize their metrics are off, they quickly have to devise new methods of assessing risk.

“Policymakers in the above situation are faced with two different kinds of risk. When productivity rises, driven by changes in economic structure, strong monetary tightening based on the assumption that the economic structure has not changed would constrain economic growth potential. On the other hand, a continuation of monetary easing would allow asset price bubbles to expand if the perception of structural changes in the economy was mistaken.”

“This issue can be regarded as similar to a problem of statistical errors in the test procedure of statistical inference. A type I error (the erroneous rejection of a hypothesis when it is true) corresponds to a case where (though a “new economy” theory may be correct) rejecting the theory means the central bank erroneously tightens monetary conditions and suppresses economic growth potential. A type II error (failure to reject a hypothesis when it is false) corresponds to a case in which a bubble is mistaken as a transitional process to a “new economy”, and the central bank allows inflation to ignite.

Given that one cannot accurately tell in advance which of the two statistical errors policymakers are more likely to make, it is deemed important to consider not only the probability of making an error but also the relative cost of each error. In this regard, Japan’s experience suggests that making a type II error is fatal compared with a type I error when faced with a bubble-like phenomenon. For monetary policymaking at that time, it seemed pragmatic to flexibly adjust the degree of tightening while paying due attention to not only a type II error but also a type I error.”

Sadly, we made the type II error here. That is, mistaking a bubble for a new economy. These mistakes prove even more destructive. Assuming we followed the type I error the worst thing would have been slowing economic growth when a new economy was here. Yet there was no new economy so this error is largely irrelevant for comparison. Both Japan and the U.S. largely mistook a bubble for a new economy. That is another reason current monetary policy is largely impotent in fixing the current issues.

“It seems most practically feasible for a central bank to deal with asset price bubbles from the viewpoint of contributing to the sound development of the economy through the pursuit of price stability. However, it might be the case that achieving low measured inflation in the short term does not necessarily ensure sustainable stability of the economy.”

“Within the framework of the Taylor rule, Bernanke and Gertler (1999) argue that it is possible for a central bank to deal with potential inflationary pressure in a pre-emptive manner. This is because effects of asset price fluctuations are included in changes in the current output gap. They present simulation results that the BOJ should have been able to achieve better performance if it had pursued a Taylor-type rule that discards asset price fluctuations (Figure 11). In fact, their policy rule points to the need for rapid tightening by raising the interest rate from 4% to 8% in 1988, despite focusing only on the inflation and output gap.”

Ironically, Ben Bernanke is cited in this paper discussing tighter monetary policy! The big mistake is the metrics used to measure inflation and housing prices were wrong and if we used say a modified CPI with the Case-Shiller Index for housing prices, inflation would have been much higher thus forcing the central bank to raise rates to stem the asset inflation. Because in reality, this past decade saw strong inflation if we used better measures of housing and also corrected for stagnant wages. So what we did is essentially what Japan did. Eased monetary policy while rampant asset inflation occurred even though the metrics stated otherwise.

We have many lessons to learn here. There are certainly vast differences between the U.S. and Japan including savings rates, creditor/debtor nations, and diversity of industries. Yet to quickly dismiss the lessons from Japan as unique is a large mistake, especially the monetary policy mistakes. If the past is any indicator of the future, we can expect a decade long recession rivaling the lost decade of Japan. That is, we are going to lock up our precious available capital with those most responsible for the bubble, financial institutions. You tell me how that first $350 billion of the TARP is working out?

Did You Enjoy The Post? Subscribe to Dr. Housing Bubble’s Blog to get updated housing commentary, analysis, and information.

Did You Enjoy The Post? Subscribe to Dr. Housing Bubble’s Blog to get updated housing commentary, analysis, and information.

Â

Did You Enjoy The Post? Subscribe to Dr. Housing Bubble’s Blog to get updated housing commentary, analysis, and information

Subscribe to feed

Subscribe to feed

17 Responses to “Japanese Asset Bubble: Lessons from the Economic Asset Bubble of Japan, The Heisei Boom. What parallels exist between the Japanese asset bubble and our current financial environment?”

Good article, comparisions very valid , just one glaring over sight.

You assume that all actions taken by Japan and the Fed were used to combat problems in the economy.

What if the bubbles and management problems in Japan were not errors of judgement but an experiment on how to effect a free market economy to manage to finicially enslave a democratic society and efect a new world order without the conset, or vote, of the people. In this instance all that you think of as bad or dumb moves that happened in Japan now become the exact opposite, and are the positive things that you would want to happen. Then if things happened the way you wanted in your smaller experiment you make necessary adjustments and try it out on a larger scale on your main target, the USA economy. Maybe just maybe things worked out so well in the Japan experiment that they were used almost identically on the rest of the world economy to conqurer the whole world without fireing a shot. Seems like I read a prediction like that somewhere in a 1960’s model history book make by a communist at the start of the cold war.

This might be your best post ever. I’ve been talking to folks about the Japan-US similarities, but I have not researched them in such detail. Thank you for this–it will be sent to a lot of the folks that I know.

A quite remarkable post that I have already sent to my internal mailing list. I can’t agree with you more … this truly is amazing work. I rarely comment like this though this type of content certainly warrants such.

Tragedy and Hope?…

I have a graph that displays Japanese home prices from 1980 to 2005. It has prices for the six largest cities and prices for the rest of Japan.

1980 to 1985 both west from $100,000 to $125,000.

1985 to 1990 all of Japan went from $125,000 to $180,000.

1985 to 1990 six largest cities went from $125,000 to $335,000.

From 2000 to 2005 both are back together again dropping from !50.000 to $120,000

The six major cities in Japan huge increase is like the home price huge advance In California, Florida, Nevada and Arizona. While the rest of the country went up with a more gradual increase

Excellent post, but I must agree with the last comment that all of this isn’t really by accident. I believe it is a sure way to increase the amount of indentured servants and lower wages for the working class. All of this while the tax payer takes on the future liability of the feudal banking system. I never leave comments but this research deserve my acknowledgement!

I think we will have a North American UNION. The US, Canada and Mexico will pay off all their debt when hyperinflation takes over the dollar and the peso. With debt eliminated, there will be a new currency (the Amero). We then tell the world, if they want to do business with us, they can come on back aboard. And if you don’t like it, we do have the B1B bomber!!

mucho love,

The problem is Japan has never really learned from what happened after the bubble burst they just have played it so cautious for the last 20 years nothing has happened. In my opinion it was like falling off a horse and never even looking at a horse again.

@Tom

Very insightful. I also feel that this not an accident. It is illogical to expect that brilliant men are stupid. Sometimes they might forget that the BS they are selling is BS, but not over the long haul. Obviously Maddof knew he was running a Ponzi Scheme. Think Mozilla made a miscalculation? Think Enron was a failed strategy? I don’t think so. I believe that all of the players knew what they were doing and should all be in prison for life. They all figured to get out before the jig was up. Hell, even the one’s that didn’t get out in time had friends in high places to get platinum parachutes.

Now they plan to bleed the last little bit of wealth we have left with a fools rally. Think you can time your pullout with advice from Jim Kramer? Or maybe some still believe that stocks, like real estate, only goes up and that recessions only last 12-16 months. Japan in more than a lost decade–how about a lost generation? And that is with an Industrial base second to none, trade surplus with probably every nation on earth, and they don’t even have to waste money on a huge national defense–they get their stooges to pay for that. Somehow we’re going to fare better? How? Why? When?

Good article, comparisions very valid , just one glaring over sight.

You assume that all actions taken by Japan and the Fed were used to combat problems in the economy.

This might be your best post ever. I’ve been talking to folks about the Japan-US similarities, but I have not researched them in such detail. Thanks for sharing this post.

This post is actually chilling in its implications. A Baby Boomer looking at retirement has few good options under this scenario. I must respectfully disagree with the statement “It is illogical to believe that brilliant men are stupid.” History is full of “brilliant” people who behaved in stupid ways. Illusion can overcome anyone. “Brilliant” people are not immune.

Agree, that brilliant men do stupid things, but I’m convinced it was essentially intentional crime and not an accident. The S&L crisis was also a crime and not an accident, by and large. Just practice for the big sting.

Re: 1/5–This piece is brilliant, Doc, and I’m sending it far and wide. Thank you for taking the time to lay it out in this way. You are going to save me a lot of work…and make it possible for me (and others) to use your piece as the first salvo for discussion.

~

Creating a global underclass and restoring the old institutions of indentured servitude have long been the dream of the oligarch class, and this was an out-in-the-open dream during Reaganomics. Those with the most money and power enlisted people in their own enslavement by wooing them with the promise (dream) of being rich, then by creating faut forms of wealth (like big houses with flashy crap that you didn’t own, but debt-rented).

~

It was inevitable that the bill would eventually come due, and as that started becoming obvious, all sorts of diversions were engineered, with appeals to fear.

~

I don’t think it was an accident either. But I think we’re underestimating the role of stupidity, greed, and short-sightedness in creating oligarchies.

~

For instance, Japan, when I’d bring up the example of Japan in the ’90s and early ’00s, people would reply one of two ways. Either they’d say, “We’re not Japan, we’re the USA, Japan is an island, we have ample opportunity to expand our economy right here,” or they’d reply, “Well, Japan is an island, and we effectively have islands, like LA, where They’re Not Making Any More Land.”

~

In either case, they were closed to discussion of asset bubbles entirely.

~

rose

POST YOUR SOURCES, GENIUS

SOME PEOPLE ACTUALLY PUT IN A LOT OF WORK AND RESEARCH INTO THEIR FIGURES AND INFORMATION

This Dr. Bubble is brilliant. And I believe accurate. Isn’t it amazing how no one has the answers! History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes- Mark Twain. But,

I buy alot of Larger and smaller property( bottom -fisher) and I build and rebuild, $1000.00 doesn’t go far. Real estate now( and has been! ) actually cheap! 100 dollars a square foot is less than build COST Wouldn’t it stand to reason, that if inflation is rampant and population going up, particularly

in a verticle market(limited space) wouldn’t that have to translate eventually into value. And certainly real estate is boyant with inflation. Where am I going wrong? Remember people always need a place to live. Treasury supplies dollars for rent in depression. Talk to me.

The regulator is currently using a sixtey yaer old housing model and has not come up to speed in planning terms . This is high cost in 21st century terms and does not provide adequate affordable housing options for our communities.

Regulatory negligence inphysical planning terms is the direct cause of the economic unaffordability and disfunctional housing outcomes currrently produced.

Please revisit this post/point. I believe the can-kicking via QE has only delayed our lost decade. Stock market, real estate, etc have all been reflated using ‘easy money.’ Do you agree Doc?

Leave a Reply